The recent intentional airspace penetration by a man in a gyrocopter and subsequent landing on the lawn of the U.S. Capitol, raises questions about the airspace around Washington DC.

I was recently quoted in a USAToday article, but there are a lot of altitudes and issues here so I thought I’d provide some clarification, along with some insights on flying into DC.

NOTE: The FAA and TSA regulations are lengthy and complex – the information you are reading here is not intended to replace or substitute in any way the regulatory procedures. Pilots flying into these areas are responsible for referencing the regulatory information and following all proper procedures. This explanation is provided for members of the general public and the media who are seeking an overview of the procedures for flying into Washington DC.

After 9/11 an Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) was put into place around Washington DC. Prior to 9/11, the ADIZ was primarily around the Continental United States, extending an average of 25 nautical miles over the ocean (it’s still there BTW). The ADIZ requires that aircraft must be identified and was established during the Cold War so we would know whether the former Soviet Union was flying bombers into the U.S.

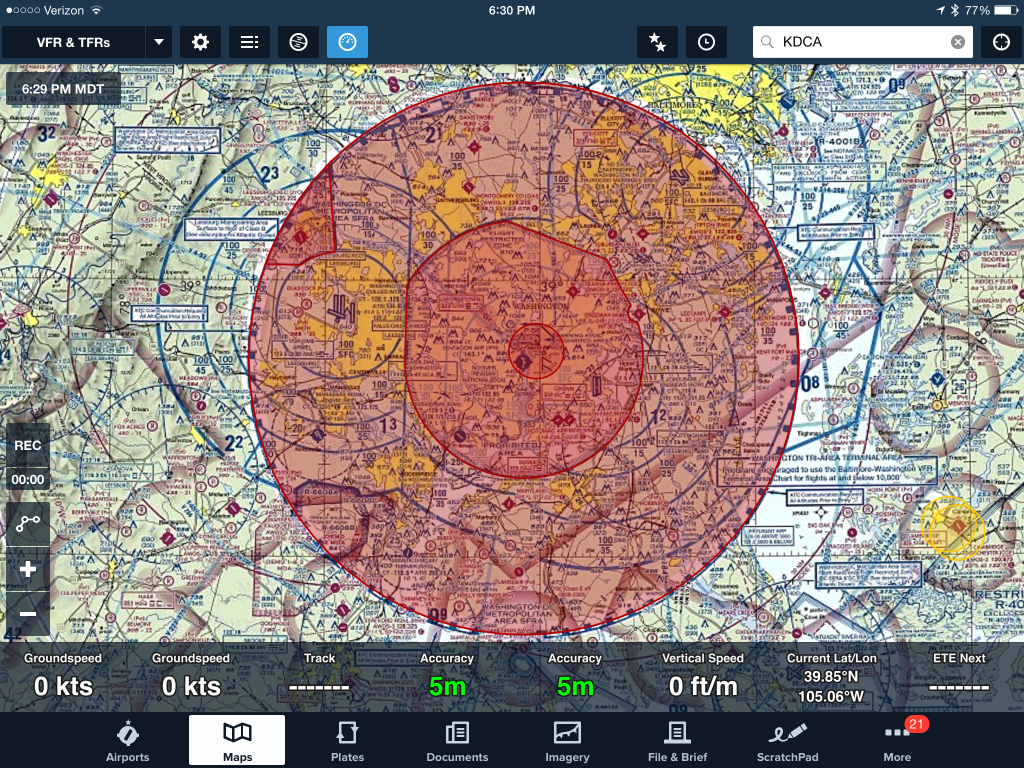

Today, that ADIZ is called the Washington, DC Metropolitan Area Special Flight Rules Area (DC SFRA) and is established as National Defense Airspace. It is the outer ring (see graphic) of airspace extending to roughly 30 nautical miles from a navigational aid that sits just north of Reagan National Airport. Use of deadly force is authorized against aircraft that pose an immediate security threat. An inner ring extending an average of 12 to 15 nautical miles is also established around Washington DC and is known as the Washington, DC Metropolitan Area Flight Restricted Zone.

There are two primary regulations that govern the airspace around DC:

- Title 14 CFR Part 93 Special Air Traffic Rules, Subpart V-Washington, DC, Metropolitan Area Special Flight Rules Area; and

- Title 49 CFR Part 1562 Operations in the Washington, DC, Metropolitan Area

Some fun facts related to this subject:

- Not every airplane in the United States airspace needs to be on a flight plan and in touch with air traffic control. This is part of the freedom of flight. There are vast areas of airspace in the U.S. where you don’t even have to talk to an air traffic controller (and we kind of like it that way).

- The rules of flight around Washington DC are different than they are everywhere else in the U.S.

- Every aircraft flying above 18,000-mean sea level must be on an Instrument Flight Plan (i.e. filed with the FAA in advance and under guidance by air traffic control).

There are essentially 3 types of aviation: commercial, military and general aviation. Commercial is mostly associated with the passenger and cargo carrying aircraft. Military is well, military, Army, Navy, Air Force, Marines and Coast Guard. General aviation is everything else and is mostly associated with private flight operations.

Passenger airliners (scheduled and charters) flying into Washington DC must be on an instrument flight plan and fly certain routes into and out of Reagan National, and be under an approved TSA security program. If you’ve ever been in an aircraft that is approaching Reagan from the north and suddenly the pilot did a hard bank over the Pentagon, you’ve been on that route.

General aviation aircraft flying into Reagan must have an approved DCA Access Standard Security Program, for which there are numerous regulations that resemble airline operator regulations (i.e. passengers must be screened prior to arrival, pilots must have undergone a criminal history record check and security threat assessment, and an armed security officer must accompany the flight).

For general aviation aircraft to fly in the SFRA around Washington DC pilots must file a flight plan, be in contact and receive approval from air traffic control and use a discrete assigned transponder code (a transponder is a radio that transmits identification information to the FAA via radar returns). Pilots must also monitor emergency radio frequencies and if intercepted by a military aircraft, follow the procedures for being intercepted.

For general aviation aircraft to fly into the Flight Restricted Zone pilots must have the approval of the FAA and TSA and be part of the Maryland-Three Airports: Enhanced Security Procedures for Operations at Certain Airports in the Washington, DC, Metropolitan Area Flight Restricted Zone. These 3 GA airports are located within the FRZ and pilots flying into and out of these airports have to follow extensive security procedures. Also, pilots must complete the criminal history record check and security threat assessment and file flight plans, and receive a briefing by the FAA and TSA on the rules of operating in the FRZ.

The Washington DC area is well covered by radar, both civilian and military. If an aircraft violates the SFRA or FRZ, an intercept aircraft is dispatched. This may be a Coast Guard helicopter out of Reagan or a fighter jet out of Andrews AFB or one of the other surrounding military bases. If the aircraft does not obey the commands, verbal over the radio or the intercept response requirements, then, according to the Flight Restriction for the area, deadly force is used.

That said, whether someone shoots down an aircraft depends on a variety of factors. In the case of the gyrocopter, and the possibility that it could have hit the Capitol, or the White House or other strategic targets, it wouldn’t have caused a significant amount of damage. It’s much more likely that the collateral damage of firing missiles at the guy, or bullets, would be much greater – or at least the risk would be much higher, than if it hit the building.

The same USAToday article did mention the possibility of using balloons with look-down radar so that inbound aircraft would have a harder time losing themselves in the ground clutter. I have some familiarity with these systems as we used to receive radar data from them back in the drug war days, when I was in the Coast Guard. While the balloon would be an additional navigational hazard to aircraft, plus a new ornament for the fine folks in Washington to view during the day, it may be time to revisit whether our response procedures are up to the task if the next airspace violation is from a much more deadly source.